Eric and I lived on opposite ends of 29th Street in Baltimore in the late 1990s. I borrowed Raincoats cds and Pere Ubu cds from him. He gave my best friend and me post-punk rarities for Christmas and accompanied us to rock shows.

Eric and I lived on opposite ends of 29th Street in Baltimore in the late 1990s. I borrowed Raincoats cds and Pere Ubu cds from him. He gave my best friend and me post-punk rarities for Christmas and accompanied us to rock shows.

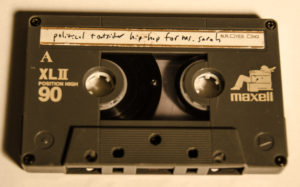

As a kid growing up in rural PA, I bought Run-D.M.C.’s Raising Hell record at the mall and was captivated by Jalil Hutchins from Whodini when he appeared on Donahue to defend rap music against Phil Donahue’s viewership. But I didn’t quite feel like I was able to figure out how to approach rap music and sink into it in the same way that I felt that I could dive deep into punk rock and new wave. I felt like a trespasser. I trusted Eric’s taste in music, and his tape was my primer on hip hop.

I loved this tape so much that it rarely left my car and started fading out from overplay. I developed a deep love for artists featured on the tape, especially Mos Def. The tape felt to me like a passport into another culture, one in which I had a friend waiting to show me around.

We sat down on November 20, 2016 to talk about this mix tape, hip hop circa 2000, how a white kid from the suburbs plunged into hip hop in the 1980s and how that interest evolved, and Eric’s curatorial approach to mix-tape making.

Sarah: Alright, so first of all, do you remember why you made this tape for me?

Sarah: Alright, so first of all, do you remember why you made this tape for me?

Eric: I was thinking about that and do you remember – was this the first tape I made for you?

Sarah: Yeah.

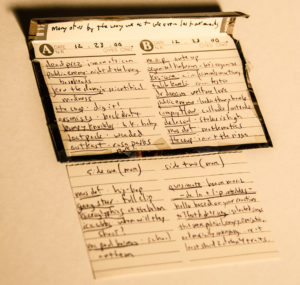

Eric: Yeah, and I think the tape must be from about 2000 because the latest songs I could find on there were from 2000, like Quasimoto and things like that. I know that in general I was making a lot of hip hop tapes for friends in that era. I’m speaking generally about making hip hop tapes for friends who are primarily in the rock scene. I was trying to bridge a gap between the political engagement we were finding in the scene in Baltimore, which seemed to at one point have lagged behind the political engagement of DC punk, but was starting to really come alive around the Bush election.

I was trying to, I guess, encourage my friends to listen to more rap. I was finding songs that – both dating back to Public Enemy but also contemporary songs that – either had a political critique to them or a musical adventurousness that I thought my friends would really respond to. So in looking back at the track list, it was a lot of songs that feel like a 101 of political hip hop in a lot of ways.

I was trying to, I guess, encourage my friends to listen to more rap. I was finding songs that – both dating back to Public Enemy but also contemporary songs that – either had a political critique to them or a musical adventurousness that I thought my friends would really respond to. So in looking back at the track list, it was a lot of songs that feel like a 101 of political hip hop in a lot of ways.

Sarah: Yeah, I think I asked you for that.

Eric: So maybe you requested that. I was intrigued looking at the track list at how well known most of those songs are. But then, there were a couple oddities. Like, “What?” [laughs] Those are probably the ones that haven’t stood the test of time as well.

But I think specifically with you, I remember you were like, “I want to listen to more rap.” And I gave you a De La Soul tape to listen to – maybe even their first album – and you were like, “No, that’s not what I want.”

Sarah: Really? I don’t remember that, but it’s entirely possible.

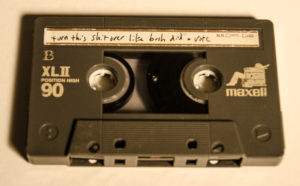

Eric: Yeah, I think I remember handing you the tape at The Zone or receiving your feedback there. But either way it was just like, “No, no. I want something that’s a little more angry.” [laughs] Like, “Why did you give me this hippie shit?” basically. I was like, “Oh, I thought this was what you’d like. Duly noted.” [laughter]

Sarah: Wow, I don’t have memory of that, but it seems entirely plausible for that period of time and what I was thinking about during that time.

Eric: Yeah, which is interesting. My relationship to commercial rap has always been kind of interesting. In high school and college, there was a lot of rap that was popular and I liked because we’re talking about from the late ‘80s into the early ‘90s. So there was a lot of music like De La Soul and Public Enemy that was commercially viable, but also felt – like with De La Soul, the samples drew on other music I liked and could respond to a lot. And with Public Enemy, I was just in awe of the power of Chuck D’s voice and what they were pointing me towards politically.

But since that era, I’ve always had a little distance between what’s popular and what I respond to, but I’ve noticed a pattern where like when Jay Z was coming out, I was just like, “No, I don’t want to listen to Jay Z. I don’t like the commercial turn that hip hop’s taking right now.” Then five years later I’m just like, “No, actually I want to listen to every Jay Z song.”

to, but I’ve noticed a pattern where like when Jay Z was coming out, I was just like, “No, I don’t want to listen to Jay Z. I don’t like the commercial turn that hip hop’s taking right now.” Then five years later I’m just like, “No, actually I want to listen to every Jay Z song.”

So I need a little distance, I think, from the music that’s popular. With Jay Z specifically, the materialism, and with some artists, the misogyny – I felt like I didn’t want to put down 15 dollars for that. Do you know what I mean? But then once I could step aside a little bit and be just like, “Well, let me find all the other things there are to love about this artist,” I would go in pretty deep.

I guess the tape that I gave you reflects that the stuff I was listening to. There was the Mos Def album, which was a huge album. But there was also the Company Flow and that kind of thing that was sort of a bubbling up of alternative hip hop. If you were to talk about ten things that were happening in hip hop from 1998 to 2001, it would be those kind of artists that would definitely be part of the discussion.

Sarah: So how did you originally get into hip hop?

Eric: Yeah, I’m trying to think. I know that when I was in middle school was when Run-D.M.C. and Licensed to Ill and things like that – the Def Jam stuff was coming out. And I did listen to that stuff, but it was probably the cycle of albums from 1989, ’90 – so we’re talking about the second and third Public Enemy albums. We’re talking about De La Soul’s debut album, A Tribe Called Quest, Paul’s Boutique – I think Paul’s Boutique was a real mind-blower for me because even liking Licensed to Ill, I just thought of the Beastie Boys as one-hit wonders or something like that.

Sarah: Yeah, yeah, they seemed that way at the time.

Eric: Yeah, right. I knew nothing of their history and I just thought they were like these brash, screaming white dudes who were trend- hopping. It was really amazing to hear them come out with one of the more complex and well thought-out rap concept albums.

All those albums I just mentioned lay a blueprint for just how layered hip hop can be sonically. Also, [all those albums were] making hip hop a music where the album format mattered as much as the 12” single, which I don’t know that it was prior to that as much. So those Public Enemy albums and De La Soul albums, A Tribe Called Quest albums are records that people really loved to listen to from start to finish in a way that – I guess Run-D.M.C. and stuff was – but I think it was primarily about individual tracks prior to that, as it is again now, by and large.

Sarah: Yeah I remember when you made me this tape- me going out and buying the Organized Konfusion cd. And then me talking to you and being like, “Actually, that ONE song was the good song.” [laughs]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TgkB06RGLBs

Eric: I think they were great artists and I liked their albums but I probably pulled a track that wasn’t representative of the rest of what they sounded like. [laughs] I was tricky that way.

Sarah: So did you have people that helped expose you to hip hop when you were growing up?

Eric: I’m trying to think about that. I had a couple older friends in high school who were into it, but I think it was something that I was exploring on my own. At the time, I went to Kemp Mill Records in Columbia. There were two kinds of music you had to ask for behind the counter: rap and heavy metal. And I didn’t listen to that much metal. I kind of liked having to – I was a 14 year old – I’d get up my courage to be like, “Yeah, I need the 2 Live Crew tape” or whatever it was. [laughs]

My homecoming song I think in 1989 was a U2 song. And then senior year it was “911 Is A Joke” by Public Enemy. [laughs] And my high school was a fairly diverse high school, but you’re sort of seeing the sea change from – even jocks, or whatever, in 1989 were probably listening to Led Zeppelin and the Grateful Dead, as I assume some do to this day – and Bob Marley and whatever you associate as jock music. But also rap was starting to become the popular music, and I think people were transitioning over to where we were by the late ‘90s, where rap was, top ten essentially.

Yeah, I remember at our school dances, everyone would get in line to do Da Butt and things like that. Yeah, it was definitely part of the popular discussion.

Sarah: Have you felt a connection to hip hop culture?

Eric: Well, yes and no. I don’t want to misrepresent any involvement. I would DJ sometimes hip hop music and sets of music that were sampled in iconic hip hop at the Ottobar with my friend DJ Mills and sometimes with my friend Dave, Secret Weapon Dave. The crowd was sometimes a hip hop crowd and sometimes wasn’t. And me and DJ Mills did a record release party for the second Quasimoto album. And we opened up for Madlib once when he came to town.

So there were times where I was DJ’ing hip hop music to a hip hop crowd or whatever, but that’s the extent of it really. I wrote music reviews for City Paper and sometimes those reviews were of hip hop records. I remember the year Mos Def’s debut album came out was the first time I believe every City Paper critic picked it as their top album of the year.

But yeah, looking back I also am very aware of how I was parochial. Or there were some ways in which my listening to hip hop was maybe slightly ahead of the curve and there were many ways in which it was actually behind the curve. I was slow to appreciate southern hip hop. I still am not well versed in West Coast, like ‘90s rap. I just never developed a taste for it, you know? So definitely there are areas of expertise and areas of disinterest.

Sarah: Right. Did you ever feel, as a white person, any discomfort or anything about being interested or involved in this particular kind of music?

Eric: Well, yeah. I mean I guess I don’t know that I felt uncomfortable. And I think that I was careful to make sure I understood that it was an interest, rather than an involvement. Knowing there were limits to my knowledge and limits to my participation.

But then also, at least in Baltimore, it tended to be pretty segregated in terms of attendance. This has changed a lot, but most of the big hip hop shows in the early to mid-2000s were at the Ottobar and had mostly white attendees. That was something that I was really aware of and really bugged by. You think about, “How am I adding to this or amplifying this by being like, ‘Oh, a white guy at this show.’”

I think that the underground or local or independent hip hop scene, whichever one of those ways you want to draw the circle, is now much more oriented towards The Crown and The Windup Space as venues. I think the crowds are much, much more diverse. And I think hip hop shows in Baltimore now are much less dependent on a national touring act coming through, which is what I think is maybe still going to, in Baltimore, draw largely a white, kind of jock crowd, versus artists that live in the community and make music here and have a regional flavor. I mean that’s typically not going to be a largely white crowd, which is great.

Sarah: Yeah, yeah. Do you have a sense of what maybe helped that shift happen?

Eric: I mean I think it’s the proliferation of venues and there being so many venues in Station North that are omnivorous in what they book and geographically central. I guess maybe with the Internet too, not only was there an independent hip hop scene in Baltimore in the ‘90s, but now a lot of the records that that scene produced are insane collectibles. And yet, even as somebody who wrote for City Paper, my awareness of it at the time was minimal. And most people in the rock scene had no awareness of it.

Now when there’s a great artist in Baltimore like Abdu Ali or 83 Cutlass or something like that, people have a pretty strong awareness, and are at the shows. And it’s a big part of our perception of what the music scene is here. I’ll again say with venues, it’s sort of a “build it, they will come” thing for Baltimore because, as I’m sure you remember in the ‘90s, there would be stretches where there wasn’t a coded venue in town that would reliably have shows. You would have Memory Lane and then they would close for nine months or you would have a warehouse space or an underground space that would have shows once a week or once a month. But what are you gonna do the other six days of the week? Now there’s 10 or 12 worthwhile venues, many of which are doing shows five to seven days a week. Sometimes that’s during cold winter months where 75 percent of the shows you put forward may be local artists. So there’s just a lot more opportunities, and bookers are booking to keep their spaces busy with whatever their best foot forward is, which more often than not, is Baltimore music right now.

Sarah: Wow, that’s great. Do you feel like your appreciation for hip hop has changed since the time you made this tape? And how?

Eric: Yeah, for sure, in so many ways. I’m not as engaged with hip hop, listening to hip hop on record, as I was back then and yet I probably went through a period where I was even more engaged in between making that tape and now. I think most people hit this point at some point where if you get deeply interested in hip hop, you hit a moment where you just sort of jump back 20 years -where you primarily listen to the soul and jazz and psychedelic records that hip hop sampled.

record, as I was back then and yet I probably went through a period where I was even more engaged in between making that tape and now. I think most people hit this point at some point where if you get deeply interested in hip hop, you hit a moment where you just sort of jump back 20 years -where you primarily listen to the soul and jazz and psychedelic records that hip hop sampled.

You might be doing it for the cheap thrill of identifying the sample at first and then that becomes largely what you listen to.

That definitely happened to me where, probably not long after making that tape for you, most of my listening turned into late ‘60s through early ‘80s music and went from listening to hip hop and punk music and noise music as my primary things to listening to ‘70s spiritual jazz and late ‘60s into the early ‘70s soul records and things like that primarily.

Sarah: Yeah, I remember. Well, actually at home, I have a stash of these [hip hop] tapes from you and then I have a bunch of Ethiopiques-type stuff on mix tapes that you made me.

Eric: Oh yeah, right. The tape I made that I probably would be most likely myself to listen to this day was one I made of Brazilian Tropicalia music. Yeah, that’s probably the tape I’m most proud of because, not that no one knew about this music, but most people’s understanding of it didn’t go much beyond Os Mutantes because their music had been re-released endlessly, first by David Byrne and then by other outfits. And I think people largely thought they were a one-off. It’s like, “Well, how was there this amazing band that sounded like the Beatles in Brazil in the late ‘60s?” But people didn’t understand it was part of a much larger scene.

At a certain point, also thanks to the internet, I found stores and eBay dealers that were importing these records and started collecting Brazilian music working off of some of the producers and side musicians that worked on the Os Mutantes and some of that stuff and just really got into it. There wasn’t much you could read in English about that scene at the time. There just wasn’t a lot of documentation. A couple years later, all of a sudden, there was a wave of just that.

There was a compilation Soul Jazz put out that was Tropicalia and I was – I don’t know, not to pat myself on the shoulder too much, but I was really excited that their two-set CD was basically like my tape. Not that they saw it, but I was just like, “Oh, I actually researched this – I did a professional job of researching this and identifying the songs people will respond to the most.” So even though their set in a way made my tape unnecessary and redundant for people who had the CD, it was still one of my proudest moments of researching something from scratch myself.

stack of tapes from eric

Sarah: Wow, I love that you remember having made that and what was on it.

Eric: Oh yeah, I mean I sort of started recently, now that people have tape players again, making copies of it again. And it was also a reminder to me how OCD I was because with most tapes I ever made, it was a goal of mine to have no filler at the end. I would often, when I was about three songs away, time how much time was left and find songs that added up just to it. Or I would find a song that I knew I could fade out at the end and it would sound like that was the end of the song. I remembered the Brazilian tape I made fit perfectly, so I special ordered – I think it was like Maxell XLII-S 90s or whatever. I was disappointed to find out it wouldn’t be 90 minutes. It would be probably like, for that brand, it would be like 91 and 20 seconds or something like that, you know? Thankfully they weren’t shorter, but they were longer. So I was just like, “This is gonna fit to the second,” and there were like 40 seconds of airtime. [laughs] I was like, “Fuck this. I didn’t spend 18 hours making that tape 15 years ago for this to happen.”

But yeah, that’s probably the tape I made ever that I was most psyched on that I would still go back to and be like, “Yes, this one.”

Sarah: We should have done the interview about that tape. [laughs) So are there songs from this tape that are still some of your all-time favorites?

Eric: Let’s look at the play list. My quick answer is probably no.

Sarah: Oh, no.

Eric: I think most of them are probably like worthwhile songs, with a few embarrassing exceptions, but I’m trying to think. It’s been only recently that I’ve been able to get back into listening to like Public Enemy and De La Soul after probably a 10 year or so gap just because- you know what it’s like when you wear something out? I definitely did that to those records.

Yeah, I mean the artists I would be most likely to listen to an album by in this day and age would be Public Enemy or De La Soul, and that’s only after taking a pretty big break. I love going to see The Coup live. That’s a really good live show still.

OutKast, I would definitely still listen to OutKast. Hieroglyphics are incredibly prolific and some of it’s great and some of it’s kind of garbage-y, but I could still listen to a lot of their stuff. Company Flow, I would still listen to a lot of stuff, El-P, his new music is still worth listening to I would say.

Sarah: Yeah, that OutKast song, that, I think, was the most crossover into popular hip hop song that you put on here. I remember listening to that in Washington Village/Pigtown in Baltimore and the kids that I had in my car with me that I was working with being really excited.

Eric: Oh, cool. Yeah, I mean if the tape made you excited about rap and maybe in a way that you weren’t before, then it did its job in the moment.

Sarah: So when was the last time you made a mix tape?

Eric: That’s a good question. I know that I was still making them probably as recently as 2010 or so. But I remember making people tapes and them looking at me like, “What am I gonna do with this?” And I started making more CDRs and playlists after those were probably outdated for people too. I never got the same satisfaction. I made a sequel to the Brazilian tape that was a CDR, and I think largely because of the format, I just wasn’t ever as happy. I tried to approach it the same way I’d made the tapes, but the tapes I would often get a third of the way through the tape and sit down and listen – very time consuming. But the thought that was put into the flow of the music and stuff was an entirely different experience and I never – The way that CDRs and playlists and these things make it easier to throw music together definitely results in a less intimate and rewarding final product. You know? They save you time and that’s really all they do.

Sarah: Yeah, absolutely.

Eric: So the tape I made of my favorite songs from the Ethiopiques series – I’m not as proud of that one as the Brazilian one because I was curating within someone else’s curation. I love the tape, but what I did was buy the first 20 volumes of Ethiopiques and then put my favorite songs on a tape. So I was working within someone else’s work. Whereas with the Brazilian one, I’m sure lots of people have had the same experience of going through those records and identifying a lot of the same songs, but I was doing it on my own without any map. That felt really exciting.

My interest in music today has a big linkage with an interest in history. So I’ll really enjoy sitting down and reading a book about – Well, just recently I’ve been reading a book called Detroit ‘67, which is largely about the changes that happened to Detroit as a city, but also to Motown in 1967 when the Supremes were having all these internal battles and Barry Gordy was starting to get pulled towards Los Angeles instead of Detroit. And Detroit was becoming much more violent. And there was a lot of problems with the auto industry that led to results we’re all aware of now.

I really love finding a nice book that engages with Stax Records or something like that and then going back to some of those albums and listening to them while reading. That kind of stuff brings me a lot of enjoyment.

As I have less time to do a lot of first person investigation myself, I also rely a lot more on compilations from Numero or Soundway or something like that, where I know really smart, tasteful people are going through a whole lot of stuff and putting together a beautiful collection of music, but also going through the photographs and liner notes that they assemble. That’s probably the closest thing I have to mix tapes these days. But unfortunately, it’s a professional curator instead of a friend doing the work. But whatever.

Sarah: Yeah, I find I’m really much less motivated to read all of those liner notes. I mean I sort of like that it’s there and I always think, “Oh, I can’t wait to read this.” And then I often don’t because there’s really not a personal connection.

Eric: Yeah, I think also being an adult and all the, on the one hand responsibility but, on the other hand, privilege that comes with it – it’s like, you’ve got kids, we’ve got jobs. We’ve also got more money than we used to. To buy an album, when I made you this tape, that was probably my album for the next couple of weeks. Now, if you wanted to you could go to the store and buy 10 albums, and then where are you gonna find the time to read 100- page liner notes for each one?

Sarah: Yeah, you’re absolutely right. Do you have any other parting thoughts?

Eric: I had no memory of what songs I would have put on this tape for you, but the fact that it still resonates with you in some way 15 years later – it’s just amazing that these things turned into objects with some permanence.

Even tapes that were lost – like I’ve got friends who lost the Brazilian tape, for instance, and were like, “Oh man, can you make me another one?” The music lives on. And the curiosity that it sparks lives on. So that’s awesome.

Eric Allen Hatch is the director of programming for the annual Maryland Film Festival and the forthcoming Parkway Theatre, opening mid-2017 in Baltimore’s Station North arts district. For many years he wrote film, music, and book reviews for Baltimore City Paper. Eric has programmed film series for the Baltimore Museum of Art, and was a founding member of the Red Room Collective, the experimental-music group behind the High Zero festival. In the virtual realm, you can find him photoshopping Paul Blart into transgressive art-house films under the handle @ericallenhatch.

Eric